The Calmness of Metal

Interview with sculptor Stelios Panagiotopoulos in his studio.

AP: Stelios, has sculpting been a conscious decision as a form of expression for you?

SP: No, I started with painting, but after my studies at Tinos preparatory Art School and my contact with marble, I chose sculpting. I saw the space in three-dimension and was fascinated.

AP: During this period, you won two awards in marble sculpting. Despite that, you finally chose to work with metal. What attracted you to metal as a material?

SP: After my studies in Tinos, I went to the Athens School of Fine Arts. During research in the various workshops, I came to the metal workshop. The students’

constructions and the smell of metal attracted me to try it, and one thing led to the other.

AP: But we are talking about two different volumes and materials.

SP: Exactly. We have two hard materials, but I believe metal is more flexible to shape than marble. While in metal, we have additions and reductions, in marble, we have only reductions.

AP: How many years did you stay at Tinos preparatory Art School? What memories do you recall of this period?

SP: I stayed there for three years and have the best memories of my life from this period. Living on a Cycladic island like Tinos with this magnificent light and do what you love. There is nothing more unique.

AP: From this point onward, your friendship started with artists with whom you created a strong bond.

AP: That’s true. In this group is Dimitris Costas.

AP: You refer to “The Five” group.

SP: Yes. Dimitris was older than me as a student. We became friends and still are.

AP: Your professor was sculptor Giorgos Houliaras. To what extent did the professor affect his student? Because I have the impression that in your first sculptures, you saw influences from his style.

SP: Of course, there is influence. You take elements from your teacher or someone you admire and add them to your work. Fermentation takes place. It’s an unconscious process in which, without any doubt, you transfer elements from the teacher.

AP: Which key element in the work of Houliaras do you believe influenced you more regarding plasticity?

SP: Definitely plasticity, gravity, the power of his drawings and volumes but foremost, the poetic mood that derives from his work.

AP: If you combined the word metal with other words, which would these be?

SP: Metal, rust. I should also add the color blue-black that the metal gives off, which I like, hardness, referring to the material, coolness.

AP: Coolness, the metal?

SP: Yes, it gives me a sense of coolness.

AP: Your answer astonishes me because, in my mind, metal as a material gives the feeling of something red-hot. It’s the first time I hear the expression “cool” for such a material, but it’s your way of seeing it.

SP: When you touch it, when it’s calm and peaceful, it’s cool.

AP: In many of your artworks, you introduce spare parts. How easy do you believe it’s for a sculptor to introduce such elements in his work?

SP: I can’t say if it is easy or difficult. It’s just an experiential matter for me happening unconsciously. As if inside me, there is something automatic that guides me. I really can’t explain it.

AP: What I am trying to say is this. Aren’t spare parts restricting the artist? It’s a ready-made material.

SP: It’s that ready-made you point out.

AP: Exactly. Whether it will be rendered correctly or not.

SP: There is undoubtedly a risk in this case.

AP: That’s what I mean. Nevertheless, you take that risk.

SP: I like to include spare parts because I see them as individual sculptural forms. I work in my brain on a sculpture I want to produce and have spare parts scattered in my studio. I see them, and there comes to my mind what goes where.

AP: Stelio, where do you usually find these spare parts?

SP: I search for them everywhere. Some people know I use them, so they bring them to me.

AP: I remember your sculpture “Explosion of Love” out of spare parts. The first time I saw it was in 2016 at the exhibition dedicated to sculptor Zoggolopoulos. It bonded perfectly with the rest of the sculptures in the room. I saw Houliaras sculptures as well. Does Zoggolopoulos as a sculptor, influence your work in any way?

SP: No, not at all.

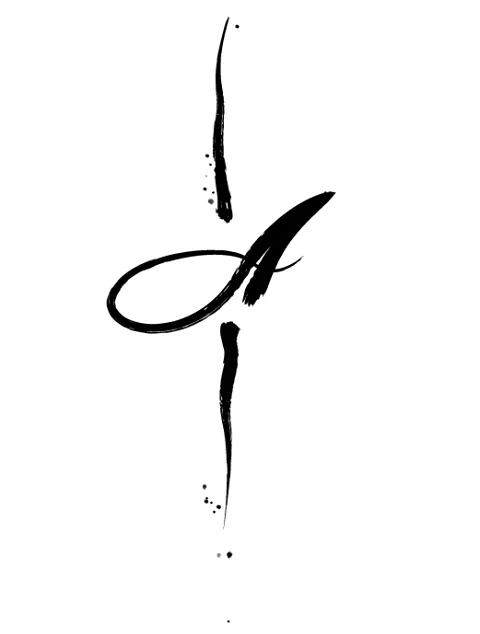

AP: In most of your artworks, you use the vertical layout.

SP: Yes, I indeed love this layout.

AP: In an exhibition catalog, I believe it was for the Zoggolopoulos exhibition, your sculptures are characterized as technological totems.

Do you see them as technological totems?

SP: Yes. I won’t disagree with this characterization. It’s in my mind such a thought.

AP: Totems are cult symbols.

SP: Yes, they are a cult symbol. Maybe the layout refers to that.

AP: When you create them, do you see a totem?

SP: No, when I create them, I don’t explain, from the start, what they will be. It emerges later. I later baptize my work. I work spontaneously, feeling it in the base of my stomach and enjoying every moment as if I am participating in a game. I don’t think at all.

AP: So, the totem is a characterization that defines your work later on.

SP: That’s correct.

AP: How do you define technological totem as a term regarding our current way of living?

SP: I worship the spare parts of a machine. That’s what I do. I take the spare part and give them another hypostasis.

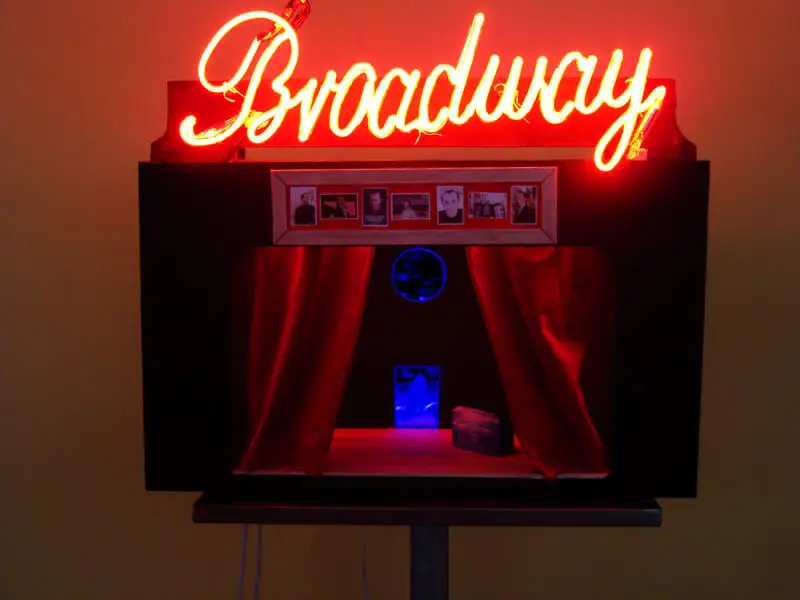

AP: In many of your works, we see fractals. Are those fractals referring to nature or mathematical relationships?

SP: I believe nature itself incorporates mathematics.

AP: So it’s a two-way connection between nature-maths and maths-nature. How did you start conceiving fractals in your work? The repetitive circles, the concentric ones, as presented in the Zoggolopoulos exhibition.

SP: I also started working on the triangular elements. The “Tree of Life” is one such example. I also used fractals there. I was influenced by nature, by a flower or a tree.

AP: What triggered the creation of the series of your works titled “Neraida”?

SP: Spare parts of the ship “Neraida” (that is, fairy in Greek). It all started with a personal relationship with someone who provided me with the spare parts without knowing their true origin. Later, I discovered that they used to be parts of the famous ship “Neraida” owned by Greek shipowner Latsis. So subconsiously, I felt I had to refer to the ship, and give a second chance to those spare parts that came out of its hull.

AP: How many sculptures have you created with those parts?

SP: I created a total of twenty-four.

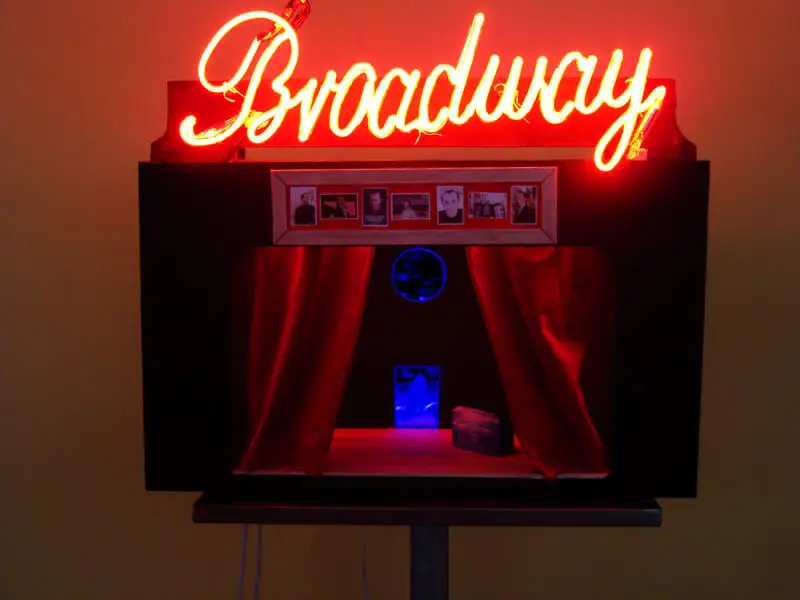

AP: During the period you created the “Neraida” series, I have seen sculptures in which you used boxes. I recall four or five years ago, when I came to your studio, that you started introducing encasing in your work.

SP: I like encaving. I like coal as well.

AP: Why do you like coal so much?

SP: I see coal as compact, solid memory.

Photos: courtesy the artist/ Photographer: Mirella Manola

AP: Regarding your encasing. Do you prefer boxes open, closed, or dark with light? Because I have seen that you added light to some of them.

SP: I am still experimenting. Nothing is clear. I am still in a continuous search.

AP: We are talking about two extreme opposites, light and darkness, and in the middle, we have coal. Another thing that impresses me is that, during our discussion, we unravel extreme opposites in your work. What triggered you to such extremes? From your technological totems, the elongated vertical layout to encasing.

SP: From art school, I started experimenting with boxes. I recall an assignment that our professor gave us to do in the workshop regarding boxes and experimentation on different materials.

AP: Since we are talking about your boxes, and as you told me, you include the concept of coal, do they include memories and moments in life? Is there an encased ego?

SP: I believe it’s true. All the elements you included are there. Memories, moments in life, my life, ego. They are all encircled in my work.

AP: Stelios, I hope you enjoyed this interview. Thank you for your time.

SP: Thank you Athina.

#athinas

Become part of athina’s team! Share your works, enthusiasm, and opinion about visual arts.

follow us

You May Also Like

Sculpting life and myth

24th September 2021

Burial Marks

6th June 2022

When you visit any website, it may store or retrieve information on your browser, mostly in the form of cookies. This information might be about you, your preferences or your device and is mostly used to make the site work as you expect it to. The information does not usually directly identify you, but it can give you a more personalized web experience. Because we respect your right to privacy, you can choose not to allow some types of cookies. Click on the different category headings to find out more and change our default settings. However, blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience of the site and the services we are able to offer. For more information please read our

When you visit any website, it may store or retrieve information on your browser, mostly in the form of cookies. This information might be about you, your preferences or your device and is mostly used to make the site work as you expect it to. The information does not usually directly identify you, but it can give you a more personalized web experience. Because we respect your right to privacy, you can choose not to allow some types of cookies. Click on the different category headings to find out more and change our default settings. However, blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience of the site and the services we are able to offer. For more information please read our