Michail Parlamas: Reconnecting with my inner child

With his artistic career so far, Michalis Parlamas deservedly represents the school created by the Greek painter and academic Vangelis Dimitreas.

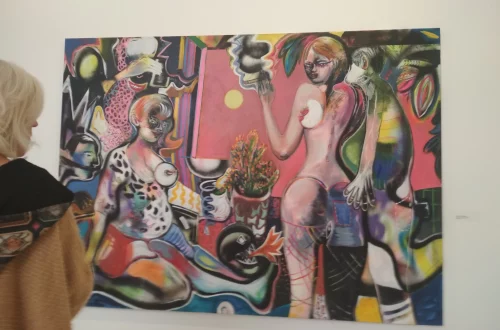

During his early studies at the School of Fine Arts of Thessaloniki, next to Dimitreas, Parlamas is introduced to the morpho-anatomical plasticity dynamics of the human body and face. He is characterised by his intense experimentation and his attempt to integrate the human figure on the surface of the paper and canvas, not as an actual representation but as an abstract design process that results in essential lines, frequently distorted.

Influenced by the experiences of the 90s generation to which he belongs together with a group of earlier students of Dimitreas as Nina Kotamanidou, Stavros Valkanis, and Antonis Migos, he is captivated by pop art. The rise of the video clip industry, MTV, the fashion of the time, and the use of computers and video games give him unprecedented stimuli.

AP: How did the new stimuli of the 90s affect your work and your love for pop art?

MP: I fell into the new generation of pop artists. Because of this xenomania that struck us, we all wanted to go abroad. We all felt that Greece did not fit us. That we were strangers in our country, tropes of the said generation.

Perhaps the extremely early stage of movements regarding the rights of women and minorities, the development of ecological consciousness, and activism in Greece at that time led the restless spirit of the then-young Parlamas to seek adventure and knowledge in London.

AP: Dimitreas was a professor generally loved by his students. What did your separation from him and the end of this period mean to you?

MP: We had acquired a parental relationship with Dimitreas. He was like the father I didn’t have. When I went to London, I felt like a child running away from my family, searching for new experiences.

He enrolls at Central Saint Martins, where he looks forward to continuing on pop art and the principles of his professor. None of this happened. He studies next to Alex Landrum, with whom he has a direct dispute. In essence, it was a dispute between two different schools of teaching and methodology on painting.

AP: When you go to London, are you completely cut off from the period of Dimitreas?

MP: I wanted to go on working from where I had stopped. Now that I think about it, I should have chosen to go to the USA. During this period at Saint Martins, there was a strong ideology that painting had died. It was hopeless for any artist to compete with the Renaissance period as painting reached its pick during that period. My professor told me that painting is quite a demanding medium, and you immediately get compared, so you mustn’t be simply good but excellent.

AP: What do you remember most vividly from the period you studied in London with Professor Alex Landrum?

MP: Alex Landrum. Very conceptual. We couldn’t agree. He had a scathing humor, very British. Imagine that during my first tutorial, he told me: “It seems as if you have puked on the surface of the canvas” After ten years, I decoded his saying. In other words, he believed that I had no methodology and that I was over-instinctive in my approach, that I immediately start and paint on the canvas as I used to do in Thessaloniki. It did me good because I got out of my comfort zone and developed a methodology. It also became so cerebral that I got to a point where

I lost all pleasure. I was thinking more about it. I got gripped by a phobia. It had become so cerebral that I had lost my spontaneity in painting. Maybe I couldn’t control it. I refer to things that happen and are uncontrollable, what we call a happy accident or the creative accident.

He finds a way out in the art of museums and galleries, the frenzy of London life, and youth hangouts without filters and defenses. He characterizes this period as experimental but necessary for his future development and course.

AP: In London, while you were hanging out and had stimuli from the Tate and other galleries, did you have something that influenced you later to draw the first pieces in pop art?

MP: I loved England as an art hub. I was interested in whatever was happening around me without defenses and filters. I started to lose myself but didn’t give up and kept creating. It was an experimental period that I think helped me figure out what it is that I don’t want to do.

During this period, his work is rashy, without a trace of concentration, and a “don’t care” attitude that is common among artists today. In East London, where he lives, he gets savagely attacked. The incident

completely changes his perception of life and art. In his attempt to overcome the incident, he introduces himself to the psychoanalytic approach of Carl Jung.

He returns to Greece and withdraws completely from all social and artistic contacts. He secludes himself in his studio, where he creates the series of works, “Gods + Monsters.” It is a dive into pop surrealism and the Lowbrow movement. Through an abundance of multicultural symbols, this captures a world of contrasts filtered through, an individual code.

SHARE THE PAGE

The excessive use of symbols that took endless hours of detailed work ceases to satisfy him. He felt it deprived the viewer of the freedom to create his own story. Thus begins the next series of works of “Floats,” using only the plastic swim ring as a symbol.

He finds a way out in the art of museums and galleries, the frenzy of London life, and youth hangouts without filters and defenses. He characterizes this period as experimental but necessary for his future development and course.

AP: How does the float become a prime element in your works?

MP: The floats were a reaction to my previous works. This overly-detailed painting approach started to become very impractical and time consuming, plus I had started to see that I was overloading my work to such an extent that the meaning behind my work was getting too convoluted.

I ultimately felt like I was guiding the audience towards a very specific narrative that I didn’t want it to have. On the contrary I wanted my work to be open to more interpretations. Therefore, I started to remove little by little elements, which eventually led to the creation of the pool float series.

He gradually reconnects with the child he hides inside him free from rules. Thus he begins to close the intellectual gap that he felt had formed between the period before and after England. The series of works titled “Floats” marks the gradual artistic turn of Michalis Parlamas during the period of the School of Fine Arts of Thessaloniki.

AP: What prompted you to re-examine the period of the School of Fine Arts in Thessaloniki and the influences you have from Dimitreas?

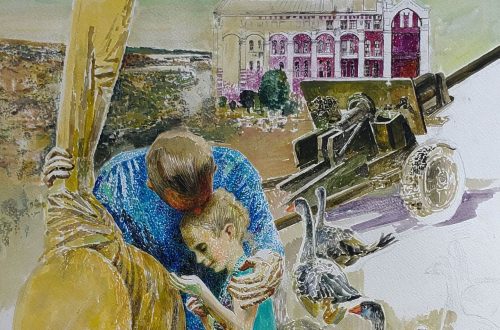

Photos: curtesy the artist/ © Michail Parlamas

MP: All this time, it troubled me very much, almost becoming tyrannical, excruciating to think that an inner gap emerged between what I used to be and what I had become after my 7 year stay in England. In other words, I felt that I had lost touch with myself. And you know something, I believe that the driving force for the visual artist – this is a personal opinion, but I think it applies to many – is the connection with our inner child.

Parlamas works on large-dimension paintings. On the canvas, he captures the freedom of expression that all kinds of rules denied him. In the series of works “Floats,” the liquid element is another indication of the new transitional period that his works are entering to reach the new series of works “Selfiesh” consisting of 10 portraits.

follow us

You May Also Like

Günter Ludwig: An alternative Ultima Cena

25th May 2023

The Oscillating Girl

17th January 2020

When you visit any website, it may store or retrieve information on your browser, mostly in the form of cookies. This information might be about you, your preferences or your device and is mostly used to make the site work as you expect it to. The information does not usually directly identify you, but it can give you a more personalized web experience. Because we respect your right to privacy, you can choose not to allow some types of cookies. Click on the different category headings to find out more and change our default settings. However, blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience of the site and the services we are able to offer. For more information please read our

When you visit any website, it may store or retrieve information on your browser, mostly in the form of cookies. This information might be about you, your preferences or your device and is mostly used to make the site work as you expect it to. The information does not usually directly identify you, but it can give you a more personalized web experience. Because we respect your right to privacy, you can choose not to allow some types of cookies. Click on the different category headings to find out more and change our default settings. However, blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience of the site and the services we are able to offer. For more information please read our