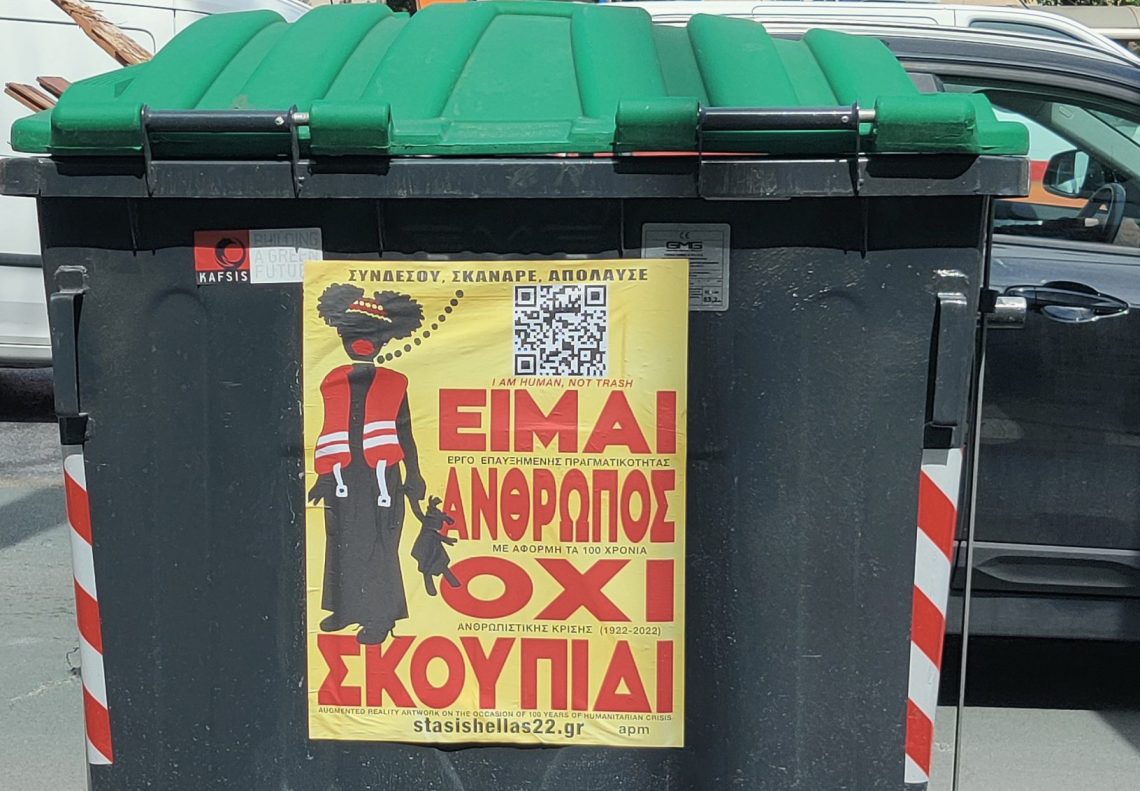

Hellada Stasinoglou: I am human, not trash

Hellada Stasinoglou is a sixteen year old girl that came to Greece in 2020. With her animation skills she describes the problems refugee children face as well as the latest political and social changes in Greece.

Hellada Stasinoglou is a sixteen year old girl that came to Greece in 2020. With her animation skills she describes the problems refugee children face as well as the latest political and social changes in Greece.

AP: Hellada, the title of your work is “I am a human, not trash.” What exactly are you referring to?

HS: My augmented poster artwork is a cry against racism, intolerance, and all forms of child exploitation, from trafficking to slavery. However, I sense most people perceive it as totally something else. Μany people stop and congratulate me without having grasped the whole message. Τhey isolate and comment only upon the political dimension of the phrase “NO TRASH”.

AP: What prompted you to tackle a topic based on three pillars: refugee, childhood and adolescence, and racism of big cities?

HS: I live in it every day. When I landed in Athens in 2020, I couldn’t believe what I saw around me. Having grown up in Shanghai and Montreal, in multicultural schools with classmates from the four corners of the world, I fell from the clouds with what I saw and read herein my parents’ country of origin. A great injustice is done primarily to children and women. But refugees are part of the future of this country. These children are ours too. Totally out of coincidence, I found myself in Greece during a period of great humanitarian crisis but also a change in the city itself. I mean that the people and the surrounding space are constantly changing. There is movement all around. What a unique opportunity to tell a story?

AP: How did you start working with film animation, and how did you envision combining it with the poster?

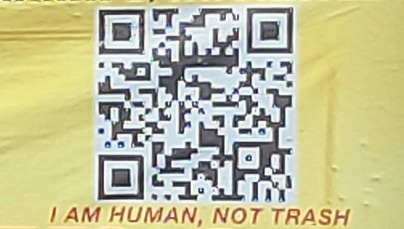

HS: When I took an animation art course in Canada, I realized I could create any world I wanted from scratch. I am fully in control and free to be spontaneous. You see, the viewer perceives animation more consciously. As somewhat abstract, the viewer must add the missing information by himself, so he spontaneously participates. He tries to fill in the missing action. That is my first goal. Then, the art should go to the viewer and not the other way around. Public space, Greek light especially, is high art in itself. What better than spreading my art across the country on surfaces no one uses and they exist everywhere? The old tech paper poster came and fitted naturally. The poster is a traditional activist city medium, as it is now the mobile phone. Because I like to combine different things and experiment with everything interesting, I decided that Augmented Reality can harmoniously bring all these together by allowing me to tell and share my story in a totally new way.

AP: In the course of your project so far, have you encountered any difficulties?

HS: The main difficulty I initially had to face was accepting the fact that some people were tearing and vandalizing my poster. And I’m not talking for the municipal employees but obviously for those who are “bothered” by my truth. But I quickly understood that this ephemeral dimension of street art is a condition imposed on you by Public Space. Now I like the idea that a total stranger spends time and touches my work. Of course, I should add that, on a symbolic level, when my poster ages, it brings out an even stronger message and bothers more.

AP: The five episodes I watched are based on a specific story. Is there a scenario in your mind? If so, in how many episodes will it be completed?

HS: I spend a lot of time on the script. It is the most crucial and creative part of the whole action. I know what I’m doing has never

been done before, nowhere, so it’s an opportunity to try and experiment. Every time I come up with an episode, I must find ways to tell the story utilizing at the same time all the possibilities offered to me by the tools of Augmented Reality. That is basically, to decide which two-dimensional elements I will project towards the viewer as three-dimensional, and vice versa. By bringing elements and information upfront and inside our physical space I thus change their relationship with the viewer’s reality. In this way, the mobile garbage bin is transformed into an installation with the viewer in a dynamic role. Probably this is close to how cinema is going to be in the future. My serial film is about the two refugees , HAYA and IZAR, from Senegal and Syria, a bit younger in age than me.

In the following episodes they will both end up as victims of pimping. Until then (no idea when and what the final episode will be) every episode is inspired by what I read and see happening around me. What is certain is that they will remain pals forever. It all starts with a boat of refugees heading toward a big luminous city and joyful skyline full of firecrackers. In the second episode a dreamscene puts us in the psyche of the refugee. In the third, I criticize state indifference and human organ trafficking. Then I touch on the relationship between policing and education. Last year’s bloody events in Persia inspired me to take a stand against an unjust law by having IZAR, in a reaction movement, to unleash her beautiful hair free in the air. Exarcheia square, the housing exploitation rings, and the children’s slavery are the focus of the fifth episode. In the background, in a wider angle, there is a city in construction orgasm, a city of sad uniformity and vanity. I therefore satirize all kinds of authority and outdated rhetoric – myself included. I never miss the opportunity to always make fun of myself.

AP: How do people, especially how do children react to your project? Do you remember a reaction or a comment that made big difference to you, an impression?

HS: I get mixed reviews. Most they agree with my poster message, while others find that there is no issue of racism in Greece. I get to talk with many different groups.

I do not feel shy and intimidated, this is my project. I also get interviews from some of them which I might include in the making off documentary I’m preparing. In whatever neighborhood I’ve been to, younger ones are much more open and willing to scan, and discuss the movie. Some also follow the story on social media. The most interesting comment came from Turkey: someone wrote that with this action, the city is transformed into a single outdoor cinema where we are called to get out of our role. Someone else from Volos commented that this is a new experience of complicity that combines walking and thinking while elsewhere they wrote that because of the augmented poster on the bins the urban information changes under our noses. But no one got into the main issue, how the poster can help things change. I think it’s too early for the Greek public. From what I read, poster as a medium in Greece does not enjoy a great tradition. And art in the street level has only just begun to take the first timid steps, and of course, who wants to approach a stinky garbage bin with a 1000 euro cell phone??? These snobs are the very kind that make me stronger. Their hypocrisy vindicates me, and thus I find the courage to continue creating.

Photos: courtesy of the artist/© Hellada Stasinoglou

follow us

When you visit any website, it may store or retrieve information on your browser, mostly in the form of cookies. This information might be about you, your preferences or your device and is mostly used to make the site work as you expect it to. The information does not usually directly identify you, but it can give you a more personalized web experience. Because we respect your right to privacy, you can choose not to allow some types of cookies. Click on the different category headings to find out more and change our default settings. However, blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience of the site and the services we are able to offer. For more information please read our

When you visit any website, it may store or retrieve information on your browser, mostly in the form of cookies. This information might be about you, your preferences or your device and is mostly used to make the site work as you expect it to. The information does not usually directly identify you, but it can give you a more personalized web experience. Because we respect your right to privacy, you can choose not to allow some types of cookies. Click on the different category headings to find out more and change our default settings. However, blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience of the site and the services we are able to offer. For more information please read our